Walk into any major psychiatric research lab today and you’ll hear less about inkblot tests and more about neural circuits, connectivity maps, and blood-oxygen signals. Mental health research has quietly undergone a revolution, and brain imaging sits right at the center of it. Instead of guessing what’s happening inside the mind based purely on behavior, scientists can now watch patterns unfold inside the brain itself—sometimes in real time.

That shift hasn’t cured depression or schizophrenia overnight, but it has changed how researchers ask questions, frame diagnoses, and test treatments. And that’s no small thing.

Moving Beyond Symptoms to Brain Systems

For decades, mental health diagnoses were built almost entirely on reported symptoms. Two people could receive the same diagnosis while having very different underlying brain biology. Brain imaging offered a way out of that dead end.

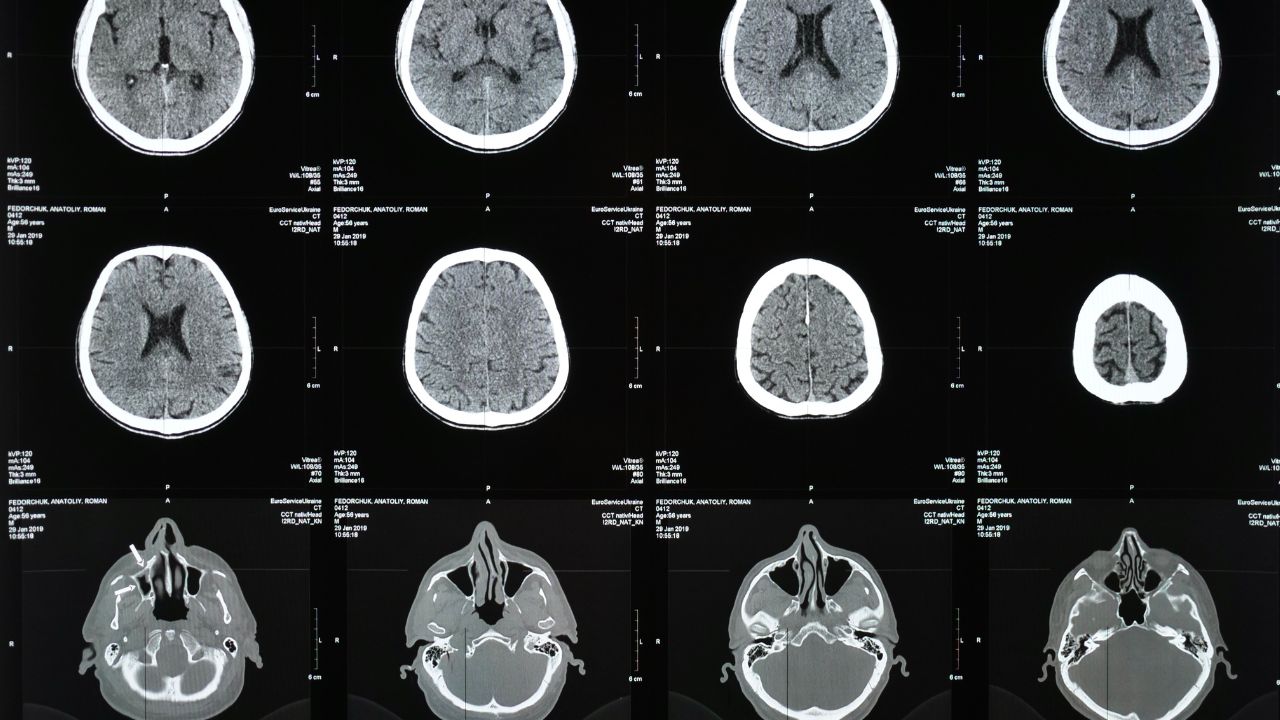

Structural MRI allowed researchers to ask whether certain disorders were linked to physical differences in brain regions. Functional imaging, especially fMRI, went a step further, examining how networks communicate—or fail to—during emotional processing, memory, or rest.

The National Institute of Mental Health has openly acknowledged that symptom-based categories alone are limited, which is why imaging plays a key role in its Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) framework (https://www.nimh.nih.gov). The idea is simple but powerful: study mental illness through brain circuits and behavior together, not in isolation.

Depression: Mapping Mood and Motivation Circuits

Major depressive disorder was one of the first conditions to be intensely studied using brain imaging. Structural MRI studies have repeatedly shown reduced volume in regions like the hippocampus, an area involved in memory and stress regulation. But structure only told part of the story.

Functional imaging revealed altered activity in mood-regulating networks, particularly the prefrontal cortex and limbic system. fMRI studies showed that depressed individuals often display heightened responses to negative stimuli and blunted responses to positive ones. In plain English, the brain’s emotional volume knob seems stuck.

PET scans added another layer, showing changes in neurotransmitter systems such as serotonin and dopamine. According to research summarized by the National Library of Medicine, these imaging findings have helped guide newer treatment approaches, including targeted brain stimulation (https://www.nlm.nih.gov).

Anxiety Disorders and the Fear Network

If depression research focused on mood, anxiety research zoomed in on fear. Imaging studies consistently highlight the amygdala, a small but powerful structure involved in threat detection.

People with generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, or PTSD often show hyperactive amygdala responses, even to neutral cues. At the same time, the prefrontal cortex—responsible for regulation and rational control—may show weaker engagement.

Functional connectivity studies revealed something crucial: it’s not just that certain areas are overactive, but that communication between regions is disrupted. The brain’s internal “braking system” doesn’t apply enough pressure. This insight has been central to refining exposure therapy and cognitive behavioral approaches, as outlined by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs in PTSD research (https://www.ptsd.va.gov).

Schizophrenia and Disrupted Connectivity

Schizophrenia research marked a turning point for brain imaging in mental health. Early structural MRI studies identified enlarged ventricles and reduced gray matter in certain cortical regions. But again, structure wasn’t destiny.

Functional imaging painted a more nuanced picture. fMRI and EEG studies revealed widespread disruptions in connectivity—especially between frontal regions and sensory processing areas. The brain wasn’t failing in one spot; it was miscommunicating across networks.

Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) became especially valuable here, mapping white matter pathways and showing reduced integrity in tracts responsible for information transfer. The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke highlights how these findings reshaped theories of schizophrenia from a localized defect to a network-level disorder (https://www.ninds.nih.gov).

Bipolar Disorder and Mood State Tracking

One of the more practical applications of brain imaging in mental health research has been distinguishing between disorders that look similar on the surface. Bipolar disorder and major depression can present overlapping symptoms, but imaging studies have found meaningful differences in brain activation patterns.

During manic states, individuals with bipolar disorder often show heightened activity in reward-related regions, while regulatory control areas lag behind. During depressive phases, some patterns resemble unipolar depression, but connectivity signatures differ.

Researchers are exploring whether imaging could eventually help predict mood shifts before they become clinically obvious. While not ready for everyday practice, these studies are actively supported by NIH-funded initiatives (https://www.nih.gov).

Brain Imaging in Treatment Development

Imaging isn’t just about diagnosis—it’s increasingly used to evaluate treatments. Antidepressants, psychotherapy, and neuromodulation techniques like transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) are now studied through pre- and post-treatment scans.

Functional imaging has shown, for instance, that effective psychotherapy can normalize overactive fear circuits, while medication may act more directly on neurotransmitter systems. In some cases, both routes lead to similar brain-level outcomes through different paths.

This has helped legitimize psychotherapy in biological terms, a shift that mental health advocates have pushed for decades. The FDA recognizes brain imaging biomarkers as supportive evidence in neuropsychiatric treatment research (https://www.fda.gov).

Resting-State Imaging and the Default Mode Network

One of the quieter breakthroughs in mental health research came from studying the brain at rest. Resting-state fMRI examines how brain regions communicate when a person isn’t engaged in a task.

This approach led to the discovery of the default mode network (DMN), which is heavily involved in self-referential thinking. In depression and anxiety, the DMN often shows excessive internal chatter, linked to rumination and worry.

Alterations in this network have been observed across multiple disorders, suggesting shared mechanisms beneath different diagnoses. That insight is pushing researchers toward transdiagnostic models—studying common brain patterns rather than siloed conditions.

Ethical Limits and Overinterpretation Risks

Despite its promise, brain imaging isn’t a crystal ball. Colorful scans can seduce researchers, clinicians, and the public into overconfidence. Mental health conditions are probabilistic, not binary, and imaging findings often overlap between healthy and clinical populations.

False positives, small sample sizes, and publication bias remain real challenges. The American Psychiatric Association has cautioned against using imaging as a standalone diagnostic tool, emphasizing its role in research rather than routine clinical diagnosis (https://www.psychiatry.org).

Where the Field Is Headed

Artificial intelligence is accelerating progress. Machine learning models can detect subtle imaging patterns across thousands of scans, helping identify subtypes within disorders. Combined with genetics and behavioral data, this approach could eventually support personalized mental health care.

Still, most researchers agree on one point: brain imaging won’t replace clinical judgment. It will refine it. Mental health lives at the intersection of biology, experience, and environment—and imaging is just one lens, albeit a powerful one.

The real impact of brain imaging in mental health research isn’t about flashy images. It’s about shifting the conversation from “What’s wrong with this person?” to “What’s happening in this brain, and how can we help it function better?” That change alone has been worth the price of admission.

FAQs:

Can brain imaging diagnose mental illness on its own?

No. Imaging supports research and understanding but cannot replace clinical evaluation.

Which brain imaging method is most used in mental health research?

Functional MRI is the most common, followed by structural MRI, EEG, and PET.

Are brain imaging findings the same for everyone with a disorder?

No. There is significant individual variation within each diagnosis.